Prime Minister Stephen Harper usually gets the best of Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau in Question Period, and their recent exchange over the niqab and citizenship ceremonies seemed no exception. After Trudeau accused the government of “going after minorities in an irresponsible way”, Harper pounced. He said the niqab is “rooted in a culture that is anti-women”, and asked why Trudeau didn’t understand that “almost all Canadians” oppose it. The implication was clear: Trudeau, the supposed progressive, was defending anti-women practices. In the moment, it looked like another win for Harper.

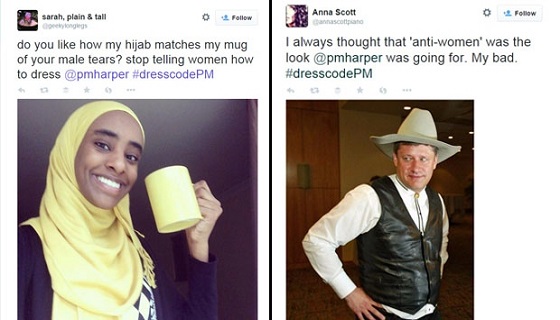

But the moment didn’t last. On Twitter, a new hashtag – #dresscodepm – was born, and within 24 hours it was trending nationwide. The PM was roundly mocked for his own fashion choices, for slandering Islam, and for presuming to suggest how women should dress. Suddenly, Harper was the one who looked out of touch.

The incident illustrates how difficult it is for governments to exert “message control” in the age of social media. Political actors have always competed for public attention and influence, of course. The successful ones dominate the medium and the message. But as Machiavelli observed, it is much harder for a ruler to hold a territory where the inhabitants speak a different language than it is to conquer the territory in the first place. He recommended establishing colonies within conquered territory, believing that colonized people will adapt the language of the colonizers, making them easier to control.

To gain and hold voter-rich territory in social media, then, it becomes all the more important for governments to control the language spoken there. Since the Harper government, and conservatives generally, are usually out-gunned in this environment, they try to protect themselves by using language that stretches the meaning of neutral words and phrases to suit their objectives, a phenomenon noted by George Orwell in his famous essay, “Politics and the English Language.”

The Harper government is well practiced at word-stretching. The titles of its legislative bills are often euphemistic pile-ups such as the Marketing Freedom For Grain Farmers Act (which eliminated the Canadian Wheat Board) or the Protecting Children From Internet Predators Act (which expanded the government’s ability to track Canadians’ activities online). Such titles anticipate negative reaction and seek to neutralize it with language that is unassailable.

The opposition MP (or Tweeter) who wants to criticize such laws is at a disadvantage before they even begin. Not only do they risk landing on the wrong side of Protecting Children or Marketing Freedom, but they inadvertently advance the government’s objectives every time they talk about it.

Perhaps the most effective – and certainly most ubiquitous – branding effort of the Conservative government was its “Economic Action Plan” in response to the 2008-09 recession. A more accurate title might have been the “Borrowing Billions to Bail Out Automakers, Build Infrastructure and Buy Votes Plan”, but obviously it would not have won the government the strong polling on economic competence it came to enjoy. The branding was so successful it still headlines the government’s economic messaging today, five years after the recession ended.

But as the niqab incident shows, government wordsmiths can’t hit home runs every time. While Harper’s “Get out of Ukraine” shot at Vladimir Putin was at least a triple, his attempt to link Trudeau to “anti-women culture” landed foul.

Another challenge facing governments is keeping up the evolution of the meanings of words. In the 500 million-tweets-a-day universe, yesterday’s term of endearment can quickly become today’s patronizing insult. Or a once-reliable insult can become a target for opprobrium. And entirely new words spring up overnight to advance political or social agendas, as occurred when advocates for the transgendered invented “ze” as an alternative to the third person singular pronouns he or she.

Certainly there is something empowering and maybe even democratizing about thousands of citizen-Tweeters picking apart a Prime Minister’s talking point, but there is also a great danger, one Machiavelli and Orwell could not have foreseen. The question is: Why should we trust these hashtag activists, these crafters of the new Newspeak, to speak truth any more than their word-twisting counterparts in government? Put another way: Harper may not speak for all women, but it’s just as unlikely that the #dresscodepm Tweeters do.

~

Joshua Lieblein is a Toronto pharmacist, blogger and political activist. He is currently serves as Research Director for the Toronto Taxpayers Coalition and the York Region Taxpayers Coalition.