The 20th Century, as Henry Luce and his prodigious legacy reminds us, was manifestly American. Who will dominate the 21st? Niall Ferguson argues it will belong to China, as did 18 of the last 20 centuries. Brian Lee Crowley and his team at the MacDonald Laurier Institute hopefully predict it will be Canada’s. But the formidable intellectual triumvirate of Daniel Philpott, Monica Toft and Timothy Shah persuasively contend it will probably be God’s.

Canada’s federal Conservative government evidently agrees, and has responded with an Office and Ambassador of international religious freedom. Created in early 2013 with a modest staff of five and budget of $5 million, it has some heavy lifting to do. Conditioned to think of political conflict in secular, ideological terms through much of the 20th Century, we have much to relearn about how to engage with religion. And in today’s world it’s an extremely delicate business, fraught with peril for secular bureaucrats and religious actors alike.

Still, this “religious turn” in Canadian foreign policy is an essential one to meet the challenge of what Scott Thomas, Senior Lecturer at the University of Bath, calls the “global resurgence of religion.” Given the real limits of secular politics, it won’t be easy for diplomats to reconcile today’s most virulent forms of political theology with liberal democracy. There might, however, be seeds for how to do so in the embryonic Office of Religious Freedom, and in a new approach to diplomacy.

In engaging religion overseas, diplomats will by necessity rely less on traditional government-to-government interaction, and more on engagement with “little platoons,” defined by their religious practice and belief. As the Institute for Global Engagement’s President Chris Seiple writes, “only good theology beats bad theology,” and only an activist Canadian foreign policy prepared to facilitate and support “good theology” abroad will have the tools necessary to do effective diplomacy in God’s Century.

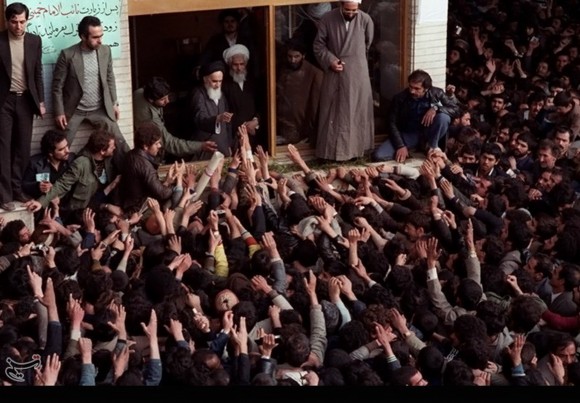

Few disagree our post 9-11 world is characterized by la revanche de Dieu, although heavyweight scholars and pundits still think of religion as a proxy for other underlying problems that manifest religiosity, like ethnic or nationalist tensions, and economic or gender inequality. Such arguments have a long and sometimes embarrassing history in North American foreign policy, not least when the CIA dismissed Islam and religion generally in the 1979 Iranian revolution as “mere sociology”.

So to argue that religion is back and that there has been, and should continue to be, a religious turn in Canadian foreign affairs, rests on understanding religion as a social and political phenomenon that is meaningfully distinct from, not merely a proxy for, other more usual suspects like poverty or ethnicity. But one should not infer that this is an unambiguous celebration of religion in politics. Some religious politics are poisonous, destructive, and degrading, and must be resisted and barred from properly functioning liberal, secular democracies, deserving of that name.

All of this is soundly summarized in God’s Century by Philpott, Toft, and Shah. The relationship between politics and religion, they argue, is neither obviously positive nor obviously negative. Whether religion is a danger to politics depends, the authors argue, on two things that may accurately predict how resurgent religion will matter in global politics: First, on the political theology of the religion, that is how religious actors perceive themselves in that context and how their faith stands in relation to it; and second, the nature of the relationship between religious and political authority.

Citing data from around the world, the authors contend that repressive or religiously exclusive governments tend to shift the way minority religious actors think about themselves and practice their religion. Depending on the nature of the repression and exclusivity, the tendency is to radicalize those minorities (or in some cases, majorities, outside the minority orthodoxy in power). Their perhaps obvious (but no less socio-scientifically sound) conclusion is that the more participation religious groups have in politics and governance, the more likely a friendly overlap of traditions and communities can be a “force multiplier” for social good.

This is not an endorsement of religious politics, but for the political engagement of diverse religious communities, bringing the full weight of their convictions to the public square. That is close to how Quebec scholars Charles Taylor and Jocelyn Maclure (in their writing about the debate over “reasonable accommodation” of religious minorities in that province) define secular societies, where secular means the area of public overlap of agreement, achieved by whatever means citizens find personally persuasive. It is also reminiscent of the great Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritan’s pithy comment about the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: “We all agree on these rights, provided nobody asks us why.”

So religion is back, neither obviously good or bad, but potentially a powerful force multiplier for social good. Strong religion and weak states is the story across much of the globe. The challenge, then, is to figure out what role such an important force should play in Canadian foreign affairs.

A secular institution like Canada’s Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development might seem ill-equipped to deal with resurgent religion. Our former ambassador to the Vatican Anne Leahy disagrees: She argues that religion was never off the radar at DFATD, but always embedded at region or country specific desks. And Andrew Bennett, Canada’s fledgling Ambassador for Religious Freedom, has said there was never a question of whether religious expertise persisted in the Department, but how best to pool and harness already existing expertise in Canadian foreign policy.

This does not mean there aren’t serious limits on what Canadian diplomats can do in God’s Century. Diplomats have no power to impose our principles like freedom of religion or belief, free markets, freedom of speech, and other indivisible human rights. Weak states might be induced to allow us to help with their constitutions, but strong religions won’t let us rewrite their theology.

This is, in fact, part of the reason why freedom of religion or belief is such an essential human right in a world awash with religious power and conviction. The only way to progress toward the universal principles Canadians so properly cherish is through religious progress. As Geoffrey Cameron and I have argued elsewhere, citing the situation in Iran:

It is a paradox not unique to Iran…that promoting religious freedom usually requires more public dialogue about religious interpretation, not less of it. The basis for restricting the rights of religious minorities in Iran is a narrow ideology, propagated by a small clerical elite that uses its control on ideas to preserve a hold on power. Alternative interpretations of Shi’ism are marginalized within the public sphere, currently dominated by discourses that perpetuate a culture of intolerance against those who do not fit within a rigid ideological cast. While Iran is rightly held accountable by international human rights bodies, to which it is a party and signatory, the long-term task of creating a society in which minorities are treated equally and pluralism is valued will require more public space in Iran for debate about Islamic theology.

The road to meeting on secular principles in Iran runs through Shi’a Islam. It is Shi’a Muslims who can reform the Islamic politics and culture of Iran, they who can challenge entrenched and monopolistic perspectives on the Islamic source and meaning of political legitimacy. There are, however, several ways Canadian foreign affairs can and should engage religion both at home and abroad – even in repressive theocracies like Iran – to encourage a meeting on secular principles.

The politics of religious engagement are often split between what is called Track 1 and Track 2 diplomacy. Track 1 is traditional state-to-state, diplomat-to-diplomat work. It leverages the conventional apparatus of the political community, rights based frameworks, and international law. This approach can yield some positive results such as getting people out of jail. But “naming, blaming, and shaming” typically has little or only short-term effect, since few political cultures respond well to public embarrassment and brow beating.

Track 2, popularized during the Cold War, is unofficial, back-channelling. It is often used by states to advance their goals through non-state actors, such as religious leaders, cultural and educational influencers, business entrepreneurs, and humanitarian agencies. It is a grassroots strategy that engages directly with local political culture and theology.

Neither track adequately responds to the global resurgence of religion, which has not only decentered the nation-state, but also blocked the regular and the back channels of diplomacy. There is no ‘red phone’ to ISIS, to radical Salafists, to Boko Haram, or to Hamas, and it is very difficult to even identify the actors who can be engaged when the groups and institutions are non-state, when their operations pivot from place to place, and when their organizational structure transcends the increasingly porous boundaries of nation-states. (As in the fluid presence of the Taliban in Afghanistan and Pakistan, for example.)

Some new, hybrid form of diplomacy is needed in the world of weak states and strong religion. Call it Track 1.5: the essential recognition that states can and must engage indigenous, increasingly highly religious, communities in the work of diplomacy. And, further, the humble recognition that state actors themselves may not be best placed, may in fact be badly placed, to do any more than merely facilitate the political-theological hermeneutics and innovation necessary to root fundamental human rights – including religious freedom – in indigenous logic and rationale. In short, official foreign policy partnerships must take many and variable forms, not merely with religious communities in their specific regions of interest, but with those communities in other regions who may have the capacity, insight, and literacy necessary for effective engagement which state actors lack. A parallel idea, advanced by DFATD policy analyst Marketa Geislerova, advocates for the use of diaspora religious communities at home to engage their counterparts abroad.

Here the Office of Religious Freedom yields just such an emerging model of engagement, through consultations and conferences with religious communities at home, and the support, via its Religious Freedom Fund, of political-religious actors abroad, who are working to build secular-consensus toward Canadian principles. More than four-fifths of the Office’s budget is actually dedicated to the Fund, and several rounds of funding have now been completed.

In August 2013 funding was announced for projects in Nigeria, Eastern Europe and the South Caucasus, and Indonesia. The project in Nigeria, where thousands have been killed in sectarian violence between Christians and Muslims, is being delivered by The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, which is developing conflict mediation capacity between religious leaders, while training up to 10 senior government officials on religious conflict resolution. Work in Indonesia includes a partnership with the SETARA Institute for Democracy and Peace for “an increased understanding by religious communities of their constitutional rights”, and “the provision of advocacy and networking tools to religious communities,” including “training for teachers on tolerance and pluralism.”

In April 2014 two projects in Pakistan received funding. One is working with religious and political leaders on human rights, including religious freedom, while the other is documenting testimony about injustices faced by non-Muslim religious minorities. And in October 2014, funding was announced for several projects led by the Catholic Near East Welfare Association to deepen inter-cultural and inter-religious dialogue in Ukraine, where enmity between the Catholic and Orthodox churches is part of the larger West-East political and ethnic divide.

This is Track 1.5 diplomacy in action. Its goal is to build sustainable environments for religious freedom using both the top-down (Track 1) and bottom-up (Track 2) approaches. The former equips governments to steward religious freedom; the latter equips citizens to exercise religious freedom responsibly. It is intended to nurture a stable state rooted in peaceful social discourse.

This kind of foreign policy is a gamble, and it all may sound a bit woolly and fluffy to hard power enthusiasts. But the work of promoting and building an international system in sync with Canadian principles in the 21st century cannot only be done from 40,000 feet. Canada does have an obligation to resist religious violence through force of arms, but defeating radicalism will take more than fighter jets. It will also require that, in the words of Thomas Farr, we get “deep into the guts of religion,” leveraging not only our communities and expertise at home, but also our friends and partners abroad. And it will mean strengthening our own Dominion, so it reliably serves as the best example on how people of diverse traditions and cultures can embrace Canadian principles. Even if we never fully agree on the reasons why Canadian virtues are so essential, we must continue to build a robust civil and social architecture that showcases how people with deep differences can live well together.

~

Robert Joustra (PhD, University of Bath) is co-editor of God and Global Order: The Power of Religion in American Foreign Policy, and author of a forthcoming book on religious freedom in Canadian foreign policy. He is assistant professor of international studies at Redeemer University College, a fellow with The Review of Faith & International Affairs, and a fellow with the Center for Public Justice.