Many Albertans want to be free. What do they mean?

Do they mean free from Ottawa? From equalization, emission caps, single-use plastic regulations, and federal environmental assessment? Alberta has legitimate grievances against the intrusions of the federal government. But if Ottawa went away, Albertans would still not be free.

Albertans should escape the Canada that is outside Alberta. But they should also purge the Canada that is inside Alberta. Alberta, like Canada, has a Westminster-style system of government. Alberta, like Canada, is ruled by the Crown. Alberta, like Canada, has a socialized system of public benefits. Alberta, like Canada, has different rights for different groups of people. Alberta, like Canada, has a managerial state that supervises, directs and controls the people. Whether government runs from Ottawa or Edmonton, living under the thumb of a modern technocracy is not freedom.

For Albertans to be free, what is the alternative?

Some might aspire to anarchy. In a state of anarchy, there are no governments and no rules. Anyone can do anything. But that includes the freedom to be violent. In a state of anarchy, you are subject to the force of other people. Might makes right. You may be able to fight back and defend yourself, but eventually the powerful make rules for others to obey. If you are subject to the force of others, you are not free.

Yet democracy also runs on force. Managerial governments, elected by the people, use laws to impose their own priorities. Laws are enforced with force: police, courts, tickets, summons and prison wardens. Rules, restrictions, requirements, policies and taxes depend on force. No force, no law. If anarchy and democracy are both violent, how can Albertans be free?

The first step is to separate from Canada to become an independent country. The second is to adopt a new and different constitution that ensures the freedom of Albertans. Below are 13 parts of this new Constitution.

1. Force and Threats of Force Prohibited

Freedom means not subject to the force of others. The Constitution’s first rule:

1. (a)

No one, including the state, shall impose force or threats of force against the person or property of any citizen without consent.

The exception proves the rule:

(b)

Notwithstanding (a), proportional force or threats of force may be used to repel imminent force in self-defence, to defend others or to protect property.

2. Using Force to Enforce the Rule Against Force

If the rule prohibiting force is to mean what it says, it must be enforced. Enforcement of any law requires force. It may not always be used but the potential is always there. Without it, the rule is just a suggestion. Some people will ignore it.

To enforce the rule, we need a state. If people were empowered to enforce the rule directly themselves, we would get violence, not peace. Anyone could bring force to bear against enemies on the pretence that they violated the rule against force. The unscrupulous would use the rule as a weapon against the innocent. Those victims, in turn, might respond in kind, triggering a violent free-for-all.

The state can enforce the rule:

2.

Notwithstanding the prohibition against force in 1(a), the Alberta Executive may use proportional force or threats of force to investigate and prosecute alleged violations of 1(a), and to enforce orders of the Alberta Judiciary.

3. The Meaning of “force and threats of force”

Article 1 prohibits force and threats of force. What does it mean?

3.

(a)

(b)

(i)

voluntary action that results in contact or interference with person or property by physical or technological means without consent. Without limiting the generality of the foregoing, force includes physical contact, whether for beneficent or harmful purpose, medical treatment, genetic manipulation, physical restraint, confinement, detention, confiscation, theft, surveillance, the use of biological agents and breach of privacy;

(ii)

(iii)

(iv)

(v)

imposing legal sanctions such as arrest, fines and imprisonment.

(c)

“Threat of force” means words or actions that promise, suggest or imply the imminent use of force, as defined above. Without limiting the generality of the foregoing, threats of force include verbal, written and symbolic communication as well as measures used to enforce laws such as tickets, summons, court orders, injunctions and police directions. Threat of force does not include expression of views that are derogatory, offensive or hateful unless the expression promises, suggests or implies the imminent use of force.

In practical terms, what does this mean you cannot do? Some examples. You can’t strike others, or even touch them, without their consent. You can’t take their things or trespass on their land. You can’t hit them with the ladder you are carrying, even accidentally, without being liable for their injuries. You can’t produce smoke or pollution that interferes with use of their land. You can’t restrain them or lock them away, even if you are the police, without due process. You can’t contaminate the river for downstream riparian owners. You can’t persistently shout in someone’s face. You can’t breach a contract that has been partially performed. You can’t make threats to attack someone. You can’t pay or encourage someone to commit an assault. In Canada, the law already purports to prohibit most of these actions. Much of the common law is based upon the central notion that you cannot impose force on others.

Governments have become the biggest threat to liberty. Constitutions grant them open-ended authority to, for example, provide for the ‘Peace, Order, and good Government of Canada’ or, in the U.S., to provide for the ‘general welfare’. Good government and general welfare, like beauty, lie in the eyes of the beholder.

However, in Canada the law also prohibits many things that Article 1 of this Constitution (the rule against force) allows. Some examples of the additional freedoms. You can sell eggs and milk without a licence. You can build a shed on your land without a permit. You can slander your neighbour, and he can slander you. You can induce someone to break a contract. You can offend to cause distress. You can discriminate in your private and business affairs. You can use, buy and sell recreational drugs.

These actions do not impose force on others. Some people might regard them as objectionable. In a free country, their distaste is irrelevant.

4. Citizens Subject to No Other Laws

Article 1 prohibits force and threats of force. Laws depend on force. The state can use force only to enforce the prohibition on force. Therefore, citizens are subject to no other laws that govern their conduct.

4.

5. Flipping the Default

We now have a state. That may be necessary, but it is also a problem. The state needs to be powerful enough to keep the peace, but not powerful enough to threaten the freedom of the people.

In Western countries, governments have become the biggest threat to liberty. Constitutions grant them open-ended authority and then attempt to curb it. The Canadian Constitution gives to the federal government the mandate to provide for the “Peace, Order, and good Government of Canada”. The United States Constitution grants Congress the power to provide for the “general welfare”. Good government and general welfare, like beauty, lie in the eyes of the beholder.

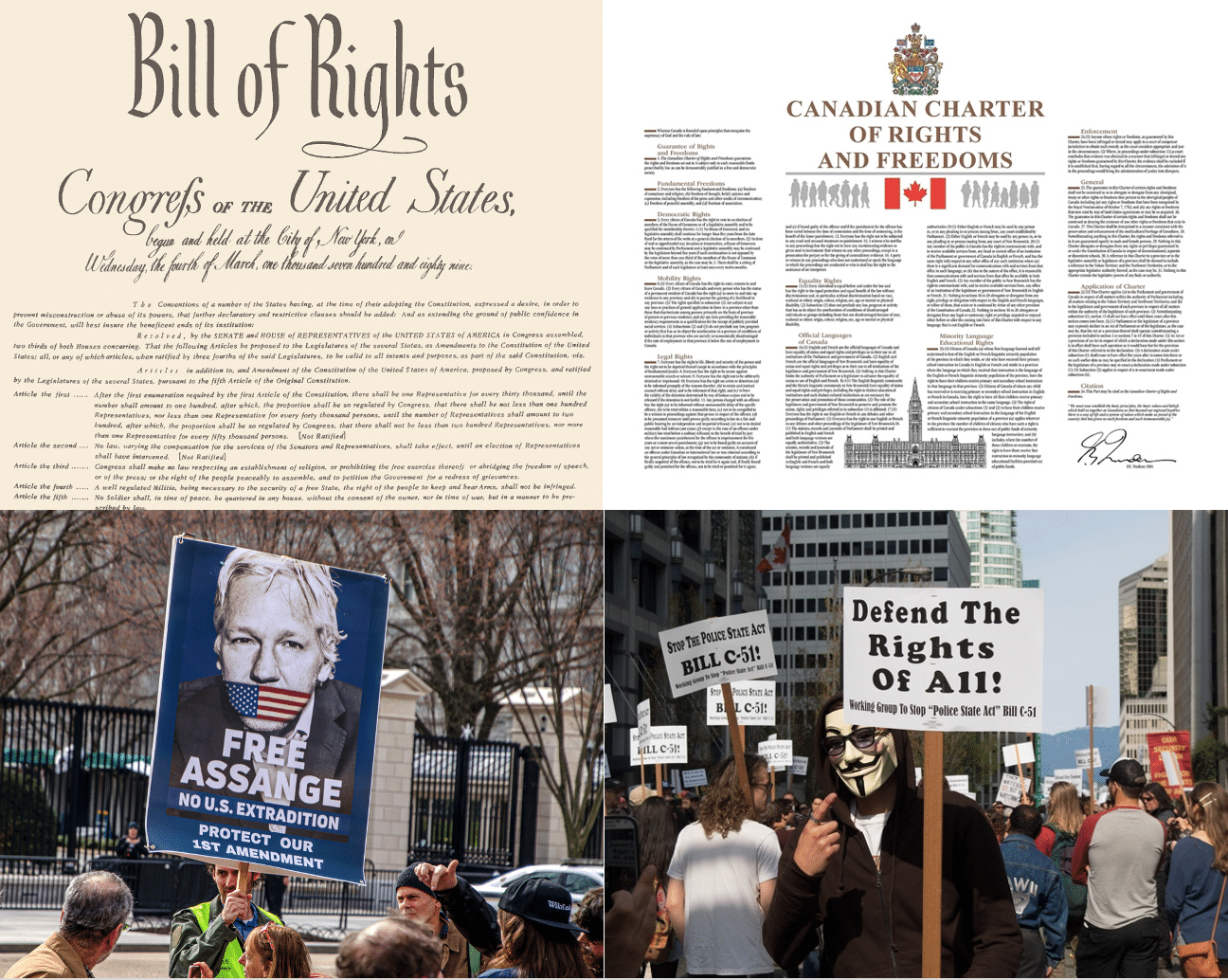

Constitutional rights carve out limitations. The American Bill of Rights and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms attempt to draw lines constraining how far the state can go. The state can do anything except, for example, infringe freedom of speech. But courts, also part of the state, control what the rights mean. Neither the courts nor the rights have prevented government intrusion into the nooks and crannies of daily life.

To keep the state in check, this Constitution “flips the default.” It does not grant the state open-ended jurisdiction and attempt to add exceptions. Instead, it makes the state powerless except for powers expressly granted.

5.

No part of the state, including the Legislature, Executive, and Judiciary, alone or in combination, has powers or jurisdiction except as expressly provided in this Constitution. No part of the state has power or jurisdiction to provide for the common good, general welfare, public necessity or emergency.

This Constitution will grant the state jurisdiction to do three main jobs:

- Keep the peace – police enforcing the prohibition on force.

- Resolve disputes about the use of force – courts.

- Protect the country from outside threats – military, borders, international relations and visitors.

If the state has only those powers expressly granted, what can it not do? It has no power, for example, to expropriate property. To collect taxes. To create public institutions. To establish or operate public health-care services, public schools or welfare programs. To regulate speech. To provide subsidies or grants. To prohibit citizens from “discriminating” in their personal or business affairs. To create monopolies, including on intellectual property. To issue currency, whether paper, coin or digital. To borrow money or incur debt. To establish a central bank. To compete in the economy. To restrict people to their homes. To close businesses. To recognize any group of people, including “Aboriginal peoples”, as distinct from any other, or to grant them different rights or entitlements. To restrict firearms, except where someone has been convicted of using force or threats of force. To require vaccinations or other medical treatment. To restrict the use of fossil fuels. To require building-inspections. To collect or store information about citizens, except to investigate crime and in court proceedings.

And so on. This list is not exhaustive. This Constitution does not enumerate restrictions. When the state is without powers, the number of things it cannot do is infinite.

This Constitution does not include “constitutional rights” like a charter of rights. There is no need. Rights like “freedom of expression” and “freedom of religion” would undermine the new default. In a state that is powerless except for the powers expressly granted in the Constitution, including a list of things the state cannot do would be redundant, long and incomplete. We cannot today imagine some of the things that technocracies will acquire the capacity to do in future. Moreover, Article 4 already confirms that citizens are subject to no laws governing their conduct except as expressly set out in the Constitution.

Enumerated constitutional rights chop freedom into bits. We have come to think of the bits as the thing itself, but they are not. Freedom of expression is but a consequence of being free. You can speak without restriction not because you possess “the right to free speech” but because you are free from the force of the state, which therefore has no means to censor you.

What would be needed for Alberta separatism to create a new country that is truly free and independent?

To truly achieve Alberta independence, it’s not enough for the province to separate from Canada. It must adopt a new constitution, markedly different than Canada’s, that ensures the freedom of Albertans and does away with the managerial state that supervises, directs and controls the people. Canada’s current constitution gives government and judges open-ended authority to set the rules and intrude into the nooks and crannies of daily life.

6. Term Limits: Amateur Public Servants

Having a state, even one with limited powers, invites a powerful class to run it. Career politicians. Tenured judges. Untouchable bureaucrats. Petty functionaries. Over time, such people create powerful institutions. A permanent civil service. Captured regulators. The biomedical state. The military-industrial complex. The deep state.

These actors use their status to enrich and empower themselves. Lavish benefits and pensions. Regulatory expansion. Growth of the public sector. Revolving doors between agencies and corporations. Lawfare. Subsidies. Pork-barrelling. Preferential laws. Bought influence. Insider contracts. Crony capitalism.

Article 5 flips the default, disempowering the state. How can the Constitution also disempower the people who run it? The way to avoid the tyranny of a professional ruling class is not to have one.

6. (a)

(b)

Notwithstanding (a), no person shall serve the Alberta Armed Forces or the Alberta Police Force, or a combination of them, for longer than a cumulative total of 15 years over their lifetime.

By removing the incentives to become a public servant for any reason other than public service:

(c)

(d)

Under this Constitution, state actors are not powerful. They are not around for long. They do not have careers as politicians, public servants or judges. Legislatures cannot pass laws on most subjects. Bureaucracies cannot make policies that tell people what to do. And as set out in Article 8 below, no elite group of judges can dictate the meaning of the Constitution.

7. Branches of the State and Elections

Article 5 flipped the default on state power and people’s freedom. Article 6 set lifetime term limits on anyone working for the state. Article 7 establishes branches of the state and rules for elections.

The Alberta Legislature:

7. (1)(a)

(b)

(c)

Senate: representation by territory. Alberta shall be divided into 50 Senate Electoral Districts of roughly equal physical size. One Senator from each District shall be elected every third year by citizens resident in that District. Each citizen over the age of 18 shall have one vote.

The Alberta Executive:

(2)(a)

(b)

(c)

All persons who serve the Alberta Executive in any capacity do so at the pleasure of the President, who shall have the power to dismiss them without notice and without cause.

Constitutions have an Achilles’ heel. They are written in words. Words have inherent ambiguities. Courts interpret what the words mean. They can give constitutions the meaning that judges prefer. Law is not a collection of rules but a language within which skilled jurists can bob and weave.

The Alberta Judiciary:

(3)(a)

The Alberta Judiciary shall consist of an Alberta Appeals Court of one judge for every 100,000 citizens, and an Alberta Trial Court of one judge for every 10,000 citizens. No other Alberta courts shall exist.

(b)

The Alberta Appeals Court shall consist of an equal number of judges from each Senate District (plus or minus one, if the number does not divide evenly). Each judge from a District shall be elected every sixth year by citizens resident in that District. Each citizen over the age of 18 shall have one vote. Elections for judges of the Alberta Appeals Court shall be staggered every third year, with half of the seats on the court to be elected in each election. Judges of the Appeals Court may or may not be lawyers.

(c)

The Alberta Trial Court shall consist of an equal number of judges from each House Riding (plus or minus one, if the number does not divide evenly). Each judge from a Riding shall be elected every sixth year by citizens resident in that Riding. Each citizen over the age of 18 shall have one vote. Elections for judges of the Alberta Trial Court shall be staggered every third year, with half of the seats on the court to be elected in each election. Judges of the Trial Court may or may not be lawyers.

(4)

Conduct of Elections:

(5)

8. Disempowering Judges

Constitutions have an Achilles’ heel: they are written in words. Words have inherent ambiguities. Courts interpret what the words mean. They can give constitutions the meaning that judges prefer. Clear and precise drafting helps, of course, but even when the meaning of a provision is clear, courts have the power to decide that it is not. Courts interpret constitutions, the story goes, bound by judicial limits. Precedent, logic and the rules of statutory interpretation restrict their discretion. But that story is a fairy tale. Methodological trappings do not compel judicial conclusions. Law is not a collection of rules but a language within which skilled jurists can bob and weave.

In Canada, the Supreme Court has the last word on what the Constitution requires and prohibits. Over time, the Court has expanded its own control over Canadian society. And, of course, the Court is itself part of the Canadian state. The Prime Minister controls who gets appointed to the Court. Once on the bench, judges can remain until age 75. The Court, not the Constitution, determines the limits of state power.

How can the Alberta Constitution limit the power of judges to control the meaning of the Constitution? Under Article 5, the Alberta Judiciary consists of the Trial Court and the Appeals Court. Article 8 describes the judicial process:

8. (a)

All cases heard by the Alberta Trial Court shall be heard by a panel of two judges. Cases shall be assigned to judges randomly, in an open, public and transparent process conducted by the court’s Chief Administrator, appointed by the President with the approval of the Senate. To find for the prosecution in a criminal prosecution or for the claimant in a civil action, both judges shall concur in the result. Decisions shall be written.

(b)

The Alberta Appeal Court has the jurisdiction to hear appeals of any case or interlocutory matter decided by the Alberta Trial Court. Litigants may appeal to the Appeal Court as of right. The Appeal Court shall apply an appellate standard of review. All cases heard by the Alberta Appeals Court shall be heard by a panel of three judges. Cases shall be assigned randomly, in an open, public and transparent process conducted by the court’s Chief Administrator, appointed by the President with the approval of the House of Representatives. For the appellant to prevail in any appeal, all three judges must concur in the result. Decisions shall be written. Decisions of the Appeals Court are final and cannot be appealed further.

(c)

Precedent is the idea that courts should be consistent from case to case. “Like cases should be decided alike.” Precedent is a feature of the rule of law. If courts follow the reasoning in previous cases, then the same reasoning applies to everyone. Following precedent provides certainty and stability in the law. It decreases discretion and arbitrariness. That’s the theory.

But not the reality. Precedent does not provide certainty and stability. Instead, it concentrates power in the highest courts. It gives the Supreme Court of Canada power to control the law and the meaning of the Canadian Constitution. Lower courts may have to follow the Supreme Court, but the Supreme Court does not have to follow itself. Because the Court is the apex judicial authority, there is no effective check on its power. Precedent does not protect people against arbitrariness. Instead, it subjects them to the arbitrariness of the judges at the top of the judicial heap.

(d)

If there is no binding precedent, judges in each case interpret the words of the Constitution for themselves. That will not provide certainty or guarantee consistency from case to case. But it will ensure that no small group of judges can control and change the meaning of the Constitution by judicial fiat.

How would a constitution designed for Alberta independence prevent such things as crony capitalism and the dominance of a professional ruling class?

A constitution designed for Alberta independence could prevent the formation of a professional ruling class by making public service a temporary duty rather than a lucrative career. It could have lifetime term limits of six years for any person serving the state in any capacity, including as President, Senator, judge or employee. To remove financial incentives, all public servants could be paid an amount equivalent to the national median wage and would be prohibited from receiving pensions, bonuses or any gifts or payments from third parties.

To dismantle the system of crony capitalism, where politicians and corporations empower and reward each other, a new constitution could specify that only human beings are legal persons, with the legal capacity to own property, make contracts, sue and be sued. Citizens would no longer be mere cogs in the wheels of a managed society dominated by entities that the state creates.

To summarize:

- Judges are not appointed but elected. A different set of constituents elects judges to the two courts. Each judge of the Appeal Court is elected in a Senate District. Each judge of the Trial Court is elected in a House Riding. (Article 7)

- Judges need not be lawyers. (Article 7)

- Judges can sit for a maximum of six years over their lifetime. (Article 6)

- Each case is assigned randomly in a public and transparent process. The person conducting the assignment process in the Trial Court is appointed by the President and approved by the Senate, and in the Appeals Court appointed by the President and approved by the House. (Article 8)

- To reach a verdict of guilty or liable, both judges on each Trial Court panel must agree. (Article 8)

- To overturn a decision of the Trial Court, all three judges on each Appeals Court panel must agree. (Article 8)

- Decisions of both courts must be written. (Article 8)

- No decision is binding on a future court. (Article 8)

The managerial state dominates our lives, but so do its creations. Big governments and big corporations are in business together. Corporations fund politicians and regulatory bodies. Governments fund and favour companies and industries. They are beholden to each other.

9. Only Human Beings are Legal Persons

We need a big, powerful state to protect us from big, powerful corporations. That’s one of the arguments. But without the state, corporations would not exist. Corporations are a product of the law, and law is a product of the state. Legislation gives corporations legal existence. Likewise with unions, charities, foundations, central banks, municipalities, universities, school boards, Indian bands, political parties and professional regulators. They have legal capacity to own property, make contracts, sue and be sued.

Moreover, they have other powers and rights that human beings do not. Corporations can accumulate capital beyond the capacity of any individual. They provide their investors with limited liability. Unions counterbalance corporate might by representing workers without their individual consent. Central banks issue fiat currency and control the money supply and the interest rate. Like Dr. Frankenstein’s monster, these entities are more powerful than people.

The managerial state dominates our lives, but so do its creations. Big governments and big corporations are in business together. Corporations fund politicians and regulatory bodies. Governments fund and favour companies and industries. They collude to manage economic activity. They leverage each other’s political power. They share expertise and personnel. Governments and corporations are beholden to each other.

Corporations are efficient. By providing limited liability to their investors, they can pool more capital, control more assets and employ more people than any single proprietor. They can achieve “horizontal integration” (producing a wide array of related products) and “vertical integration” (owning and operating their own supply chain) to an extent that individuals cannot match.

But efficiency is not liberty. Rank-and-file citizens cannot compete. They are second-class participants in their own economies. They are mere cogs in the wheels of a managed society dominated by entities that the state creates.

In a free country, only human beings have legal capacity. Accordingly:

9. (a)

Only human beings are legal persons. No other entities have legal status to own property, make contracts, have standing in court or do any other thing.

(b)

Notwithstanding (a), the Legislature, the Executive and the Judiciary each is a legal person for the purpose of fulfilling the functions set out in this Constitution. Each has the legal capacity to sue and be sued.

(c)

Article 9(a) applies to domestic and foreign entities. Foreign judgments in favour of non-human legal entities shall not be enforced in Alberta.

People are free to cooperate, to build businesses, to make contracts, to invest together and to associate as they wish. They can, by contracting with each other, organize and run commercial enterprises. But their contracts do not bind other people, and organizations that they create do not have legal existence. In Alberta, the state cannot grant legal personality to non-human entities.

10. Citizenship

Western countries have low birth rates. Their citizens are not procreating fast enough to replace their aging populations. The low birth rate has served as one of the main rationales for rampant immigration. Western governments have flooded their own countries with newcomers so fast and in such numbers that their cultures are now in doubt. Some of these countries may already be past the point of no return. But these phenomena – low birth rate and influx of immigrants – are two sides of the same slow-motion crisis. Healthy cultures reproduce. Ultimately, every society faces a choice: procreate or perish. The self-immolating state must not be allowed the power to determine who can be a citizen. Accordingly:

10. (a)

After adoption of this Constitution, children born inside Alberta to at least one parent who is a citizen at the time of the child’s birth are citizens. Children born outside Alberta after adoption of this Constitution to at least one parent who is a citizen at the time of the child’s birth shall be granted citizenship upon application. There shall be no other path to becoming an Alberta citizen after adoption of this Constitution.

(b)

Laws and courts shall apply the same legal tests and standards to every citizen, with the exception of minors and the incapacitated. No law or court shall take account of the identity, background, race, lineage, culture, origin, ethnicity, religion, gender, sex, sexuality, wealth or status of any citizen.

11. Separation of Powers

Different parts of the state do different jobs. That is the principle of separation of powers. The legislature legislates. The executive executes. The judiciary adjudicates.

In theory, separating powers keeps us safe from tyranny. Legislatures make rules without knowing the future disputes to which they will apply. Government agencies enforce rules without being able to control their content. Courts apply rules to cases without having a hand in their formulation. No one institution has control. Separating powers protects citizens from those who would tell them what to do.

Separation of powers is a well-established constitutional principle. In the United States, the President is the head of the executive branch but does not sit in the legislature. Even in Westminster-style systems, where the same individuals head the legislature and executive, executive action requires statutory authorization, at least in principle.

But in Canada, separation of powers has been eviscerated. Legislatures pass statutes that delegate to government agencies the power to make laws. Executive bodies make the bulk of the rules. Cabinets, ministers, departments, agencies, commissions, professional regulators, municipalities and many more produce regulations, policies, guidelines, bylaws and directives of all kinds. Delegation is the lifeblood of the administrative state. This problem is addressed through:

11.

The Alberta Legislature shall not delegate substantive law-making or adjudicative authority to any part of the Alberta Executive or to any other person. No part of the Alberta Executive shall make substantive policy decisions, fill substantive gaps in legislation or act as a quasi-judicial body that adjudicates claims or disputes.

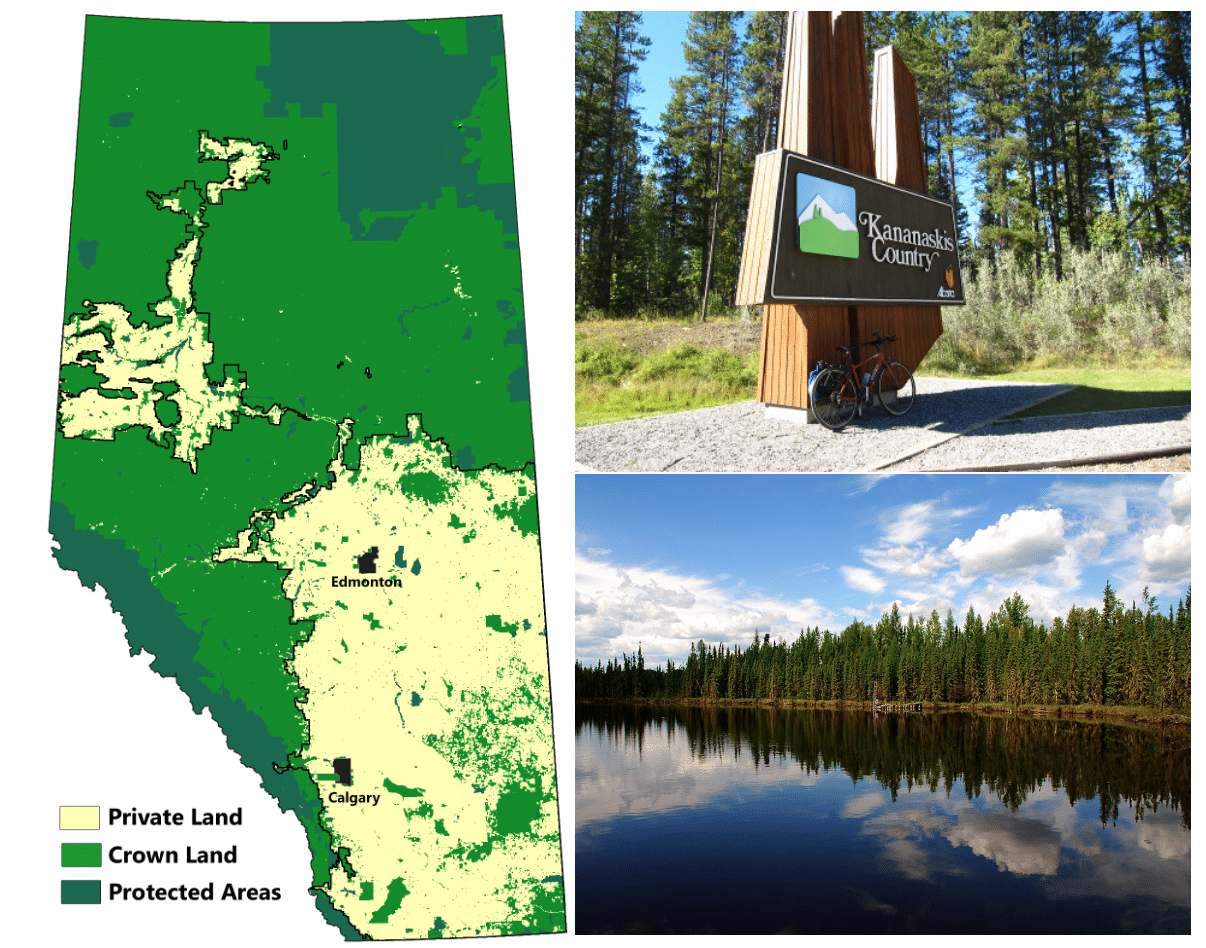

12. “Crown Land” and Other Transitions

(a) Crown land and funding the state without taxes

Even a minimal state costs money. But citizens are subject to no laws other than the prohibition on force. Without force, the state cannot collect taxes. How will the state in the new, independent Alberta fund itself?

In Alberta, as in other Canadian provinces, the provincial Crown owns most of the land (in Alberta over 60 percent). But free countries belong to their citizens. Governments should not own the territory and should not participate in the economy. Land, resources, infrastructure and utilities should be privately owned in an unregulated market. Ideally, in the transition to an independent Alberta, the government would divest its assets, including transferring property in Crown lands to individual Albertans.

But getting from here to there is not easy. In a free and independent Alberta, the Crown would not exist. If the Constitution instructed government to put Crown lands up for auction, much of Alberta could end up in a few wealthy hands. Moreover, foreign interests might fund individual Albertans as middlemen to buy up the territory on their behalf. If, instead of auctioning off assets, the Constitution stipulated that each citizen receive a parcel of Crown land of roughly equal size, randomly assigned, some would receive valuable oil sands deposits and others a useless scrap of bush. The luck of the draw is not a fair way to grant valuable assets to some and not others.

The new Alberta state could retain ownership and control with a mandate to administer those lands in the public interest, such as in a “sovereign wealth fund”. But that would amount, essentially, to the status quo. Public interest is a chimera that masks a discretionary, managerial mandate. Citizens would be mere observers on the sidelines, with no role to play over the lands that are supposed to belong to them.

(i) Grant citizens beneficial interests

One solution could be to grant each citizens a beneficial property interest in those lands presently held as Alberta Crown lands. Each beneficial interest would constitute a one in 4,600,000 share (or whatever the population of citizens is at any moment). Each beneficial interest would expire on the death of the citizen. A new interest would spring into being for each newborn citizen. Each would be able to sell, gift, mortgage or otherwise deal with that property interest as with any other. Except that no one could pass it down in their will, because the interest would expire on death.

Annual revenues from the use of these lands would, first, fund the operation of the Alberta state, and second, be distributed in equal amounts to beneficiaries. Beneficial interests would be non-possessory but would entitle their holders to the benefit of the lands – in this case, the proceeds of its productive use, whether mining, forestry, farming, grazing, recreation or the like – except that those proceeds would first fund the operation of the state. The Alberta Executive would be the trustee of the lands and, as such, would owe fiduciary duties to every beneficiary.

The problem with this approach is that it leaves supervision of 60 percent of Alberta in the hands of a bureaucracy. It would allow the government, albeit as trustee, to participate in the economy. It would create precisely the kind of role for state authorities that this Constitution aims to eliminate.

(ii) Distribute to each citizens a parcel of comparable market value

An alternative would be to grant to each citizen over the age of 18 a parcel of Alberta Crown land of roughly equal market value. Two separate processes would be required, one to assess value and divide into parcels of comparable worth, and the other to randomly distribute one parcel to each citizen.

This approach has problems too. Complete transparency in market valuation and random distribution would be required. A government authority of some kind would be needed to administer this divestment, creating potential for corruption or abuse. Citizens over 18 would be enriched, while citizens 17 and younger would have to hope to inherit. Moreover, another source of funding for state operations would be required.

How serious is Alberta separatism?

Alberta separatism is often dismissed – even within the province itself – as the domain of a few deluded rural hardliners. But the sentiment and the movement have only grown since the federal election brought another Liberal government, led by Mark Carney, to power. Bruce Pardy, one of the country’s senior legal scholars, believes it is time for Alberta to prepare – seriously, definitively, foundationally – for independence, including putting together the architecture for the constitution of an independent, and radically free Alberta.

(b) Other transition issues

Independence would require careful transition on other fronts as well. I will not attempt to list or describe the necessary provisions, but here are examples of questions that they would need to resolve:

(a) Who qualifies as the first citizens of the new country?

(b) Most existing statutes will be repealed but a few will be preserved and amended. Some parts of the common law will be retained. Which is which?

(c) When do public institutions, corporations and other non-human legal persons cease to exist? How do they distribute their assets before winding up?

(d) How shall current First Nations reserve lands be divided into lots and title granted to individual members of Aboriginal bands?

(e) How shall existing pension funds be transferred to their beneficial owners?

13. Amendment

To protect the Constitution, but also to preserve democratic self-determination, amendments to the Constitution should be difficult but not impossible.

13.

Conclusion

This Constitution is not complete. Gaps remain. But these 13 elements are the bones. They create the constitutional architecture for a free country.

These proposals are not what people are used to. Albertans resistant to change may perceive some as a bridge too far. But to go where you have never been, you must do what you have never done. Western civilization is unravelling. Alberta can be the beacon in the dark. But only if it corrects mistakes that are bringing other nations to their knees. Constitutions do not protect freedom when they simply express limits on what the state can do. State actors do not honour such limits. Instead, they believe that they are in charge. Under most constitutions, they are correct.

But, perhaps, not in a free and independent Alberta.

Bruce Pardy is executive director of Rights Probe and professor of law at Queen’s University.

Source of main image: Canva/AI Image Generator.